| Home | Architecture | Art | Books & Maps | Manuscripts | Historia da Ethiopia | Credits & Contacts |

The Jesuits and Ethiopian Art In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius of Loyola set the basis for the Jesuits’ use of imagery in their global missionary enterprise, recommending an active “application of the senses” at the end of each day in order to visualize the divine. In their drive to uphold Counter-Reformation policy, spread Catholic values and assert the authority of Rome, the Jesuits made widespread use of Loyola’s approach to sacred imagery as part of their missionary strategy, copying and disseminating certain favoured iconographic types around the world, particularly the icon housed in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, dated c. sixth century AD but believed to have been painted by Saint Luke himself. Francisco Borja, the third Jesuit general, obtained permission from Pope Paul V to have an exact copy made, which became the prototype for the mass production of painted and engraved copies which were sent to Jesuit provinces around the world, from Brazil to Japan. In Ethiopia, devotion to Mary had always been intense. King Zara Yaeqob (1434-68) insisted on the presence of a portrait of Mary during Mass, and supported a system of courtly art patronage which led to the production of an increasingly large number of Marian paintings, many of which done in tempera on gesso panels by the talented monk Fere Seyon. The Santa Maria Maggiore image, introduced by the Jesuits in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, became extremely popular in Ethiopia, and came to supplant all other representations of the Virgin and Child. Since it was primarily a vehicle for its Eastern Orthodox theological and liturgical content, Ethiopian art was by its very nature conservative. The Jesuits, however, although expelled by King Fasiladas in 1633, left a lasting but subtle mark on Ethiopian visual imagery, paving the way for the acceptance of a few new iconographic types. Both Mary’s Dormition and her Assumption, for instance, gained renewed popularity in the seventeenth century, being now depicted in substantially different ways from the earlier Ethiopian portrayals based on Eastern and Byzantine traditions. Another significant iconographic change was the well-known early sixteenth-century Flemish-Portuguese representation of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, wearing a crown of thorns. Known in Ethiopia as the Kwerata Reesu, it became an object of special veneration which Ethiopian emperors carried into battle. The establishment of a settled urban court life in Gondar in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries led to a flourishing of Ethiopian liturgical, musical and artistic life. New churches were built, musicians and dancers employed, and writing and painting scriptoria set up, which produced large numbers of profusely illustrated works, from gospels and hagiographic texts to narratives of the miracles of Mary and Jesus (Tamra Maryam and Tamra Iyasus). The Jesuits’ introduction of collections of prints like the Evangelicae Historiae Imagines (Geronimo Nadal, 1593), which they presented to King Susneyos in 1611, had an impact on the development of Ethiopian painting by providing new sources of imagery, transforming somewhat the previous lack of interest in any form of naturalistic representation of the physical world. Jesuit influence in the seventeenth century thus contributed to the formation of the so-called First Gondarene style, which introduced a few iconographic and compositional changes into the long-preserved traditional taste for flat areas of saturated colour and linear designs placed against empty backgrounds. Gradually, during the 18th eighteenth century, this style became softer and more modulated, with a greater degree of light and shading, more profuse ornamentation and more complex spatial settings, trends which define the Second Gondarene style. In both these phases of Gondarene painting, some garments, poses and decorative motifs appear to have been derived from India and Indian painting, and are generally attributed to models introduced by the Jesuits from their base in Goa. There had long been a history of contact between Ethiopians and the Muslim rulers of India, however, so the existence of direct Indian sources independent of Jesuit mediation cannot be ruled out. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

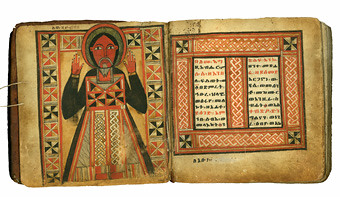

Various Liturgical Prayers, Litanies and Readings Ethiopian Manuscript on Vellum Second half of the 19th century but with four late 15th century paintings attributed to the Fere Seyon school 104 leaves, 210x270 mm Private Collection Although an invocation contained in the text dates most of this manuscript between 1855 and 1889, two sets of paintings [f. 4v, f. 46 r-v] can be dated to the late 15th century on the basis of both their pictorial and palaeographical style. These four paintings display the formal characteristics developed by Fere Seyon, court painter to King Zara Yaeqob (1434-68), and his followers: crisp lines, three-quarter profiles, the particular way the hair and beard are depicted, the gestures and poses of the figures. The picture on display here (f. 46r) shows Christ in Majesty, appearing within a mandorla flanked by two archangels who appear to be presenting this vision to the viewer. Underneath Christ’s apparition, two apostles are represented in awe, their raised gazes and dramatic gestures drawing the viewer’s attention towards Christ on the majestic throne above. The painting reflects the visionary tone that dominated north-eastern African Christianity, from Coptic Egypt to the Old Nubian kingdoms and Ethiopia. The vision of God’s throne is a widespread iconographic motif in all three areas. It is a recurring feature of Ethiopian hagiographic narratives, which often describe it in detailed and flamboyant language, reflecting the complex mixture of Judaic and Greek sources that underlie Ethiopian cosmological notions. This painting’s composition, in two registers, recalls a two-tiered design that had been widespread in Coptic apse-compositions of the seventh century, which sometimes conflated aspects of Christ’s Ascension and his Majesty in heaven – as the Ethiopian artist has also done here – to effectively convey, by pictorial means, the experience of a true theophany. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

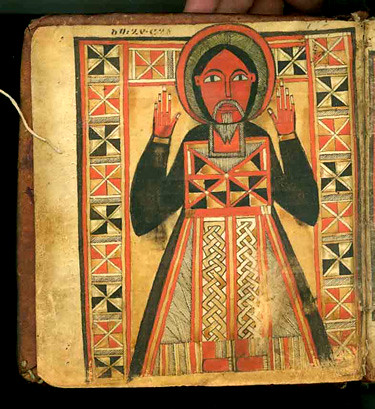

Arganonä Weddase Although contemporary with Jesuit influence in Ethiopia, this striking illuminated manuscript presents a strictly geometricized pictorial style which is entirely devoid of European elements. Its paintings and geometric pages display figures in the traditional orant position, which goes back to Late Antique and Early Christian Egyptian representations of this subject. While the figures in the Fere Seyon paintings are in three-quarter profile, revealing the influence of paintings produced in Ethiopia by European artists brought in by King Dawit I (1382-1411), here the painter has portrayed the praying figures in strict traditional frontality and placed them against a simple flat background made up of areas of red, black and yellow, which contrast with the intricate interlacing of the figures’ clothes. Such compositions preserve older Ethiopian motifs and taste, and are associated with a dozen other known works produced in the Lasta area around this time. Two of these still remain in Lalibela, but the best known example is the evangeliario kept in the British Library (Or 516), which shows a representation of Saint George and is characterized by the presence of a hornbill, defining an “artist of the hornbill” who was active in the 17th century. In the manuscript on display, this bird appears beneath the end of the text for the Friday reading [f. 123r], suggesting that it is a work by the same hand. The text – Arganonä Weddase [Harp of Praise] – is a popular Ethiopian Marian passage composed by Abba Giyorgis Saglawi during the 15th century. The original scribe’s name, Beselyos, appears on f. 123, and on palaeographical evidence he also appears to have been the scribe for the British Museum example. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gospel of Saint John the Evangelist (a.k.a. Gospel of the Portuguese Man) The writing style of this manuscript is consistent with a mid-16th century date. Although there is no colophon providing indications as to the patron, artist or scribe, other manuscripts with a similar hand are associated with the reigns of Lebna Dengel (1508-40) and Galadewos (1540-59). Possibly because the painter was aware of the Portuguese who had come to Ethiopia with Rodrigo de Lima in 1520 or Cristovão da Gama in 1541, this representation of Saint John the Evangelist is strikingly different from traditional Byzantine, Egyptian and Ethiopian portrayals. It shows the saint with European features, as indicated by his distinctive goatee beard, which was popular in the Iberian peninsula in the 16th and 17th centuries. The saint and his attendant are placed against a traditional, flat, uncoloured background, and flat areas of bright colour – including red, yellow and turquoise – make up the figures, particularly the saint’s clothes. Brilliant stars decorate the Evangelist’s gown, recalling the visionary aspects of traditional Ethiopian Christianity and the apocalyptic tone of the Revelation text in particular. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Four Gospels Produced by the Stamperia Medicea of Cardinal Ferdinando de Medici, these are the earliest Gospels known to have been printed in the Arabic language. They are illustrated with a series of engravings by Leonardo Norsino (known as Parasole) after woodcuts by the Florentine artist Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630), many of which were in turn based on illustrations made by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) for his popular Kleine Passion series (1509-11). In accordance with Counter-Reformation policy, these Gospels were widely disseminated in India and the Far East as well as north-eastern Africa, where their illustrations came to influence the development of manuscript painting in Ethiopia. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is unclear when the Arabic Gospels illustrated with the Antonio Tempesta compositions reached Ethiopia, whether during the reign of Susneyos or Fasiladas. In either case, Tempesta’s compositions were well received in the scriptoria of Gondar and, after the Jesuits were expelled, became the sources for Gospel illustrations within the Ethiopian Orthodox theological tradition, as in this well-known work. It includes portraits of the Evangelists as well as narrative pictures and, unlike earlier manuscripts, which did not integrate text and image, here, as in the Arabic Gospels, they have been integrated. The original Arabic Gospels in themselves pose interesting problems of visual intertextuality, as they include Tempesta’s Counter-Reformation version of Dürer’s much earlier German illustrations. Produced in an even more removed religious, social and political environment, the Ethiopian Gospels’ intertextual re-interpretations of the same compositions raise important questions about authorship and reception, as well as visual perception and stylistic originality. Apart from strictly theological considerations, when compared with the original scenes the Ethiopian versions show a considerable flattening of the spatial setting and figures, reflecting the painter’s lack of interest in producing an illusionistic portrayal of the natural world, which had been so fundamental to European Renaissance artists. The Ethiopian painter also placed greater emphasis on the depiction of textile patterns – reflecting, perhaps, the great importance of luxury cloth in a kingdom where, until the establishment of a more settled court life in Gondar in 1632, the rulers had been predominantly warrior kings inhabiting a mobile tent court. Written in three columns, a note on f. 238 states that the Gospels were copied for King Yohannes I (Aalaf Sagad) (r. 1667-1682) and his Queen Sabla Wangel (d. 1689). In another note, however, which gives the date 1664-65, the original name has been erased, raising the likelihood that the work had originally been started for Yohannes I’s father, King Fasiladas (r. 1632-1667). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

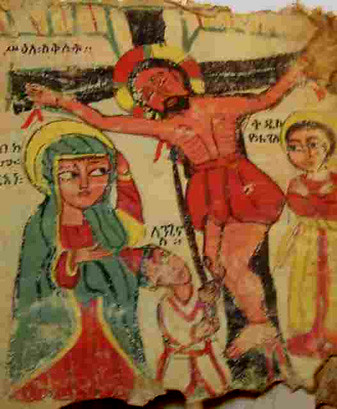

Double-sided triptych icon The earliest triptych icon of the Santa Maria Maggiore known to have been painted in Ethiopia (c. 1600) still recalls the Fere Seyon school and its crisp linear style. It places Mary and her Child against a flat red background, which emphasizes the monumental quality of these two figures, and only the apostles are portrayed on the lateral wings. Gradually, however, other figures were added to this basic composition, depicted with elongated faces that were already removed from the fuller, rounder figures of the 15th and 16th centuries. In the example shown here, the central panel portrays the Virgin and Child flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel, as would become common practice. The left-hand panel depicts Gabra Manfas Qeddus, an Egyptian ascetic saint who covered his body with just his own hair and beard and lived in the desert accompanied by two lions; this points to the continuing importance of Ethiopia’s early links with the Church of Egypt and Egyptian monasticism. Below Gabra Manfas Qeddus, a picture of six apostles signals the heavenly reward that awaits a truly ascetic life. On the right-hand side, the placing of the Crucifixion of Christ above an equestrian saint (probably Saint Theodore) spearing a man draws a parallel between the saint’s martyrdom and that of Christ. The geometrical patterning on the Infant’s garment recalls the decorative patterns of traditional Ethiopian paintings and makes a marked contrast with the European-influenced figure of Mary, reflecting this period of stylistic transition. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tamra Maryam (Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary) Throughout the Middle Ages devotion to Mary was intense in Europe, Christian Egypt and Ethiopia. A series of stories had appeared in Europe by the 12th century that narrated miraculous events mediated by Mary’s intercession. They were taken to the Middle East and North Africa by the Crusaders, where they were translated into Arabic in the middle of the 13th century. They reached Ethiopia via Egypt during the 14th century, where they were translated into Ethiopic and became King Dawit I’s object of profound devotion. Under King Zara Yaeqob (1432-68), the monarch’s drive to shape the theological and liturgical life of Ethiopia around his Marian devotion led to the miracle stories being used for liturgical purposes. By the 16th century there was a recognised canon containing 32 or 33 standard Miracles and their variations – the Tamra Maryam. Gradually many more stories dealing with local topics were added to the original canon. The largest collection known to date (British Library Or, 643, dated 1717) narrates 316 miracles. The collection shown here includes 61 miracles, although three of the stories are repeated. Twenty-six of them are part of the original canon of 32, and the names and locations in some reveal their Egyptian origin. Appealing to Mary’s intercessory power, the text of each miracle is preceded by a short formula, such as “A miracle of Our Lady, the Holy, Twice-Virgin Mary, Mother of God. May her prayers and her blessing be with her servant (named in this book as S’ewa Dengel or Abadir) for ever and ever. Amen.” Many miracles close with a short prayer or hymn to the Virgin. The eleven full-page illustrations are paintings done in simple flat areas of red, yellow and green, with lines, dots and cross-hatching. Folio 2r shows Mary as the popular icon of Santa Maria Maggiore, now flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel and accompanied by two warrior saints – in this case, George on folio 1r and Basilides on the verso – a combination that was to become widespread in icons of this period. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

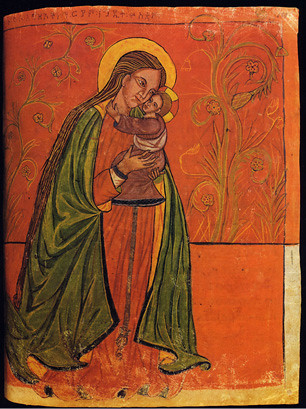

Tamra Maryam (Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary) Ethiopian, mid-17th Century (with a separate painting of Mary on parchment dated to the early 16th century – folio 180r) The picture shown here (on folio 180r) was a separate image painted on parchment in the early 16th century (as Mary’s long flowing hair indicates), which was later inserted into a Tamra Maryam done in the following century for Yohannes I and queen Sabla Wangel (as the prayer written for these monarchs on the back of the picture indicates). The tender proximity between Mary and her Child and the position of their bodies within the pictorial space recall the Byzantine Marian type known as Mother of Tenderness. During the 16th century in Egypt and Ethiopia, this type became associated with the pilgrimage to the Egyptian site of Kuskam (or Qwesqwam in Ethiopic) – the place where the Holy Family rested when fleeing to Egypt. Mary’s flowing hair and the fashion adopted for her long red robe and undulating hems point to the style of Nicolo Brancaleon, a Venetian painter who arrived in 1480 at the court of King Eskender (1478-1494) and met the Portuguese chaplain Francisco Álvares when his embassy to the court of Lebna Dengel (1508-40) reached Ethiopia in 1520. Called Marqorewos by his Ethiopian patrons, Brancaleon left a relatively large body of painted work, including a signed collection of the Miracles of Mary, now in Tadbaba Maryam monastery (Wollo). The tender inclusion of this image into the later Tamra Maryam provides a touching insight into the profound devotion which coloured royal patronage in Ethiopia, apparently overpowering any self-conscious considerations of fashion, form or style. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

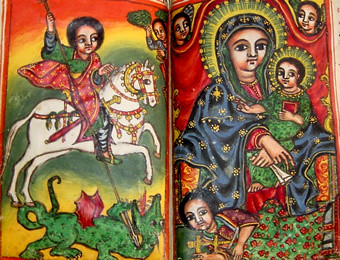

Tamra Maryam (Small Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary) The firm adoption of the Santa Maria Maggiore image revived long-standing concerns about the theological correctness of details such as the positioning of the Child Jesus on Mary’s right or left arm that had previously been voiced in response to European influences in the 15th and 16th centuries. Up until the end of the 18th century, there was no rigid rule governing this pictorial detail, although 16th-century painters seemed to prefer to depict the Child on his mother’s right arm. Following the introduction of the Santa Maria Maggiore image, however, the infant Jesus began to be almost invariably portrayed sitting on Mary’s left arm, holding a book and making a gesture of benediction. In 1769, the Scottish traveller James Bruce, who spent several years in the Ethiopian capital city of Gondar, observed that Ethiopian artists tended to rigidly adhere to this iconographic practice. The new style which emerged during the eighteenth century – now known as Second Gondarene - was defined by a much greater tonal modelling of the figures, the use of rich colours, and much more lavishly decorated compositions. Indian garments and textiles – such as those imported by King Sarsa Dengel (1563-97) – had long been worn by the Ethiopian aristocracy, and now became an important source of patterns for Ethiopian pictorial compositions. New iconographic motifs also appeared in the 18th century, including the conspicuous figure of the donor prostrated before a devotional figure – as can be seen, for instance, in the famous portrait of Queen Mentewwab (1730-69) at Narga Sellase monastery church on Lake Tana, where the Queen is depicted prostrated before the Virgin. In the picture shown here, the names of the original donor(s) have been replaced by those of Aster and occasionally Niqodimos. But an abstract idea of complete devotional surrender remains visually connoted by the figure of a donor – whoever that may be – prostrated in front of the Virgin, wearing clothes which appear to be made of luxurious Indian textiles. Mary sits against a rich crimson-coloured curtained background, which recalls 17th-century European Baroque settings for aristocratic portraiture. This aspect is reinforced by the Baroque-looking carvings that frame the Virgin’s throne. She holds a ceremonial handkerchief, an iconographic mark of high rank, power and prestige which was already present in the Christian wall-paintings at Faras, Old Nubia (present-day Sudan), in the 11th to 13th centuries. On the opposite page, there is the well-known representation of Saint George on horseback spearing the dragon, which so often accompanies the Tamra Maryam narratives and the Marian icons produced during this period. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

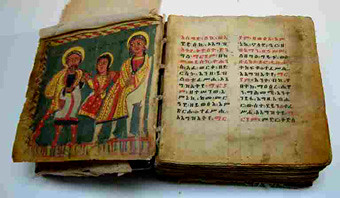

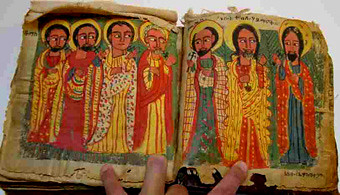

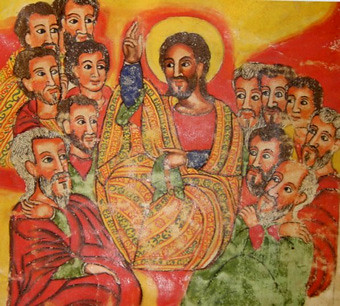

Tamra Maryam (Miracles of Mary), together with various other Marian texts The manuscript is a collection of different Marian texts – the Prologue to the Miracles of Mary, the Prayer of Mary on receipt of the Covenant of Mercy from her Son (Kidana Mehret), various hymns to the Virgin (salam and esagged), the Homily to the Virgin Mary (Dersan), the Prayer of Mary at the tomb of Our Lord at Golgotha, and the Mas’hafa Ser’at, a text that accompanies the Weddase Maryam (Praises of Mary). The text of each Miracle is preceded by a variety of short formulas like “A miracle of Our Lady Mary. May her prayer and her blessing be with her servant [name] for ever and ever. Amen.” They reveal the deep devotional attitude that characterized the readership for such works, and provide a poignant reason for the many erasures and replacements of the names of the book’s successive owners and their relatives, all of whom would have hoped to gain the Virgin’s blessing and protection by this means. A note of ownership even threatens anyone who might “steal the book or erase it” with excommunication “by the power of Peter and Paul”. An additional note indicates that at some point the manuscript was donated to a church named Dabra Iyasus by Walatta Takla Haymanot, a woman whose name occurs over many erasures, together with her father, brother and mother. The series of paintings collected here includes the portrayal of Jesus preaching to the Apostles (folio 3v), placing the devotion to Mary within a wider Christological context. This is further reiterated by the depiction of the Covenant of Mary (Kidana Mehret) on folio 9v, in which Christ acknowledges Mary’s role. In the former picture, two lines of Apostles lead the viewer’s eyes inexorably towards Jesus in the centre. This composition creates a certain illusion of depth and establishes a clear relationship among the figures by clearly directing of their gestures and gaze. In addition, delicate tonal modelling imparts an incipient illusion of bodily volume to Jesus and his Apostles, particularly their faces and hands. This painting thus reproduces some of the pictorial concerns that had been introduced into Ethiopia in foreign engravings. Rather than simply flattening the scene completely in the traditional manner, the painter unconsciously incorporates some of the representational concerns that had originally inspired these foreign models. The placing of traditional details like the handkerchief in Christ’s hand – an age-old marker of power and prestige – and the depiction of flat patterned textiles within this incipient pictorial illusionism creates a novel interpretation that is clearly representative of the complex Ethiopian cultural context of the time. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tabiba Tabiban Gondarene art reached a high point in the early decades of the 18th century, nurtured by King Iyasus I (r. 1682-1706) and King Bakaffa (r. 1721-30). Bakaffa’s wife, Queen Mentewwab (r. 1730-69), who became regent on her husband’s death, reigning with her son, Iyasus II (r. 1730-55), and remained influential during the reign of her grandson, Iyoas (r. 1755-69), was also a generous patron of the arts who left an imprint on the artistic taste of her time. Reflecting the rich cultural life at Gondar and its renewed emphasis on theological discussions, numerous beautifully illustrated books were executed under these monarchs and new pictorial cycles and subject-matter were developed, including many illustrated Lives of Ethiopian saints. Again, the influence of the Jesuits was felt through the adoption of their imagery – not directly from Geronimo Nadal’s original work but rather through French copies. Starting with the Tamra Maryam commissioned by King Takla Haymanot (1706-08), the use of such images became widespread in subsequent years. Fewer than half the available images were used, however, leading scholars like Jacques Mercier to suggest that Ethiopian theologians might have refused certain images. In any case, it was not a case of slavish copying. Rather, the Ethiopian artists borrowed selected visual motifs, re-working them into their own complete verbal-visual theological and artistic statements. Among these new cycles, the Sage of Sages (Tabiba Tabiban) covered the full extent of biblical knowledge, illustrating both the Old and the New Testaments, aiming to instruct and educate its elite readership by means of complex and obscure distichs, which echoed the metaphorical subtleties of the “wax and gold” intellectual and poetic tradition taught in Ethiopia’s most important monasteries. The portrayal of Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise re-works a composition by Abraham Blomaert, while the Evangelium Arabicum was used for some New Testament scenes like the Baptism of Christ, Christ’s Temptation, etc. and the Abrege de la Vie et de la Passion de Nostre Sauveur Jesus-Christ (1650-1660) for others, like the Annunciation and Crucifixion. An isolated engraving by Raphael Schiaminozzi, dated 1609, was also used for the scene depicting Jesus praying on the Mount of Olives. The Ethiopian artist unified these visual sources by means of a gigantic representation of Christ emerging from the clouds, which appears in each composition (but not in the original engravings), dominating it with his powerful presence and all-embracing gaze. In this inter-textual process, Christ now functions as the great narrator for the human story, visually unifying all the different narrative – and therefore temporal – moments. In visual terms, the finished Ethiopian book thus makes the whole history of humanity dependent on this Christ-centred belief to a far greater extent than the European models did. |